Helen, Heading Out (2)

A series of articles about recreating identity after an all-consuming career

By Helen

University Professor of English and Women’s Studies

Retired August 2012 at age 63

There is a crack in everything / That’s how the light gets in – Leonard Cohen, “Anthem”

In the fall of 2002, at the height of my academic career, I found myself on the outside looking in. After meetings with my GP, my Chair, my Dean, and the doctor at Occupational Health, I was suddenly on medical leave. I had no idea if it would be a week, a month, or forever. Stress, exhaustion, major depression. That wasn’t how I wanted my career to end. Lots of unfinished business. Lots of shame, however inappropriate. With my colleagues overburdened in my absence, I felt I was letting down the team.

Ultimately I was able to choose when I retired. Here and in my next installment, I want to explore the changes in my emotional life and in my relationship to work that allowed me to defer retirement until I was ready for it.

My advantages

I was lucky. I had an understanding and respectful doctor. I had a good income and savings. I had a loving partner and supportive friends and family. I had a hitherto good brain and a good education. I had race and class privilege. I had a union. I had disability insurance.

Mind you, my good income was part of the devil’s bargain made by many professionals: lots of money and no life—or at least little time in which to enjoy it. My disability insurance created problems that only added to my stresses; the ongoing need to prove my disability forced a focus on illness and incapacity at a time when my recovery depended on the opposite. Still, I was very lucky.

Coddled

A workaholic, I spent the first week of my leave disentangling myself, labouring through one last promised task. Then I could collapse. For the first week of actual recovery, I deliberately treated myself as a convalescent from surgery, lying on the couch, listening to music, and relying on my partner to feed me soft foods (coddled eggs, canned green beans – I know, I know!). Thereafter, along with the music, I listened to relaxation tapes and did daily breathing exercises and a bit of meditation. Because of the waiting list for a grief support group, I did my own grief work for half an hour or more daily, first around my mother’s death, then around the losses and pain associated with my daughter’s fetal-alcohol condition.

At the beginning, supposedly simple, restful activities like Scrabble and solitaire sometimes proved too difficult or disheartening, threatening to intensify my depression. Although I continued my routine half-hour run every weekday morning, sometimes I had to draw on reserves of willpower not to just lie down in the snow and stay there.

Learning to expect less

I attended monthly meetings of a Fetal Alcohol parent support group, a better source of helpful information and practical strategies than all the professionals. There I learned the characteristics of my daughter’s brain damage and how to accommodate them. I learned to speak less and recognize silence as companionable, to simplify her environment, to anticipate stresses, to expect less, and to make the many adjustments away from conventional parenting necessary with FASD. For my own mental health, I also learned to resist projecting into the future, to try to give up controlling what I could not, to pair stress with extra sleep, and eventually to put my painful experience to broader positive use in the community as an FASD advocate and educator.

A new balance

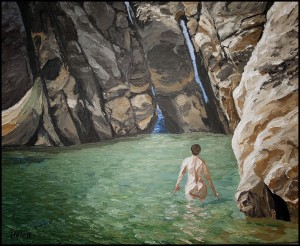

I worked my way through the many helpful assignments on creativity in Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way, a project which requires a year off work to be manageable. Three daily pages of morning notes proved therapeutic. And I took art lessons. My dream had always been to be a novelist, and I’d written a few short stories. But my own knowledge of literature inhibited me. Although I couldn’t doodle a twig successfully, a drawing class proved to me that, if I used my eye rather than my memory, I could sketch a convincing hand or bottle or human figure, even. Painting became my new creative outlet.

Exposure to a rigid form of Catholicism had alienated me from institutional religions. In the wilderness after my mother’s death, I found an earth-based spirituality, a version of paganism (though that term perturbs many), that required not belief but a sense of my place in the cycles of transformation, of the moon, of the seasons, of “birth, initiation, love, repose, and death.” I was lucky enough as well to find a group within which to practise the rituals of this spirituality. So I began balancing my intellectual life with attention to my emotional, artistic, and spiritual sides.

Undressing core beliefs

Reluctantly, but for many years, I took medication to restore my serotonin and norepinephrine levels. When the next available cognitive-therapy group turned out not to be sufficiently anonymous, I used a library CT workbook to help train myself out of damaging core beliefs. Cognitive-therapy exercises are extensive: what core beliefs underlie this feeling? What is the evidence for this belief? What is the evidence against it? What would be a more accurate formulation? How strongly do you feel the emotion now? Eventually just the threat of having to slog through the exercises would sometimes be enough to head off negative ruminations. After a series of psychiatrists prescribed by my insurance company, I continued with a counsellor covered by my Employee Assistance Plan. With her I developed a list of crisis strategies, including the employee crisis line, for the inside of my closet door. Having the list, without using it, proved sufficient. From there we went on to emotional exploration.

Hardening off & post-traumatic growth

Towards the end of my three years of leave, the insurance plan referred me to a therapist specifically for “work-hardening,” a horrifying term but fortunately with a person I could trust. We worked on approaches to reduce work anxieties, desensitize me to the campus (which I’d been avoiding), compensate for memory problems, resist obsessiveness, and modify my improvisational teaching style.

Over the years of my leave, I learned that there is such a thing as post-traumatic growth. I learned, by necessity, to balance my life, to breathe, to be mindfully in the present, to distract my amygdala (and its fight-flight-freeze reaction) with mental puzzles, to find creative and spiritual outlets, and to build a network of support. Every so often, especially after long winters, I still need to take preventative action to ward off depression.

Anticipate your cracking point

For one of my siblings and several of my friends, disability has meant the unwelcome, abrupt, early end to their work lives. So I understand that only some forms of disability can be anticipated and forestalled. In my case, I wonder if I could have protected myself better. My discoveries are nothing surprising, all familiar remedies available to me before my crisis. The lessons here are more, I suppose, about drawing on these insights before the shattering. If you want to retire only at the end of your working life, know your cracking point. And then make the changes (if those changes are within your control—and they aren’t always), while that point is still in the far distance. Resist the false assurances of your inner superwoman. Keeping work in perspective, as part of a richer, gentler life, allowed me to enjoy working longer.

Canned green beans??? Yuk!!!! Other than that, this is an inspiring article! From what you have written, it sounds as if you were able to manage your depression and exhaustion with aplomb. However, I’m sure you have not told us about many of the days of struggle and difficulty which accompanied the positive steps you took to rebuild your life. I know you are a good painter. This article shows that you are also a good writer. Maybe you have a novel in you yet!

Thank you, Amy. I still have a weakness for the occasional comfort of canned green beans–from childhood, I guess. Yes, the process of recovery was hard and I sometimes felt I was having to prove my efforts constantly to the disability insurers, probably more than was actually the case.

Helen,

Green beans or not, you are living so well! You have faced a lot with so much heart and brain and courage. Thank you for speaking up publicly, opening the crack so the light gets in farther and farther, and modelling openness for others who may be struggling and feeling alone. You have managed emotional alchemy on every front. Hurray to you. Thank you.

Thanks, Martin. Yes, let’s let the light in on these painful struggles. So much remains secret. And shameful. And lonely. I am struck in retrospect by what a worker I am, even in recovery. And you have a similar story of effort to tell.