Helen, Heading Out (4)

Helen, Heading Out (4)

A series of articles about recreating identity after an all-consuming career

By Helen

University Professor of English and Women’s Studies

Retired August 2012 at age 63

After a three-year medical leave, I’d been back at work for six years, working fewer hours, making room for other parts of my life, when in 2010 I got the offer of a buy-out package. The University wanted to cut costs by retiring senior faculty and was offering one-year’s salary and reduced pension penalties. My partner, a writer as well as an academic, at 68 had been waiting several years for such an incentive and jumped at the chance. But I had a sabbatical, or research leave, ahead that year, and the University wasn’t prepared to sweeten its offer to recognize the six years I’d worked to qualify for that opportunity. And retiring three years before age 65 meant a shockingly large, permanent reduction – by almost a third – in my monthly pension. So I reluctantly declined.

You have my attention

Unexpectedly, during my research leave, I got another buy-out offer. The expectation at universities has always been that one is required to teach a minimum of one year after a research leave before resigning or taking a position elsewhere. When I phoned about this expectation, I was told that, if I’d received the retirement offer, I was eligible to take it. Senior administrators must have been desperate. “You have my attention,” I emailed Human Resources enthusiastically, requesting the application package. And then my filled-in retirement papers sat on my desk for a month.

The push to retirement

Instead of leaping at retirement, as I’d expected, I settled in to build my pros-and-cons list.

What pushed me towards taking the offer was most immediate. Grading essays and examinations had become a torment for me. Despite forty years of experience, my concentration had worsened, so that each essay took longer, with no improvement on the quality of my comments to the students. At home, the piles loomed up dauntingly, the next course’s assignments waiting, making it impossible to crest the hill and find fewer papers ahead of me than behind. If I could have lectured and led discussion seminars without grading anything, I probably would have kept on teaching.

But there were other pushes too. Teaching is a high-energy performance. I had learned young to be a confident public speaker. My teaching style, though, offered sincerity, candour, thoughtfulness, and personal engagement, rather than the entertainment and polish of the skilled large-class lecturer. But even in smaller seminars, I found the early weeks of each semester tense, until I knew the students and we moved towards shared understandings. I taught extemporaneously, giving students tools and asking them to do the thinking, weaving in evidence and ideas to build on and extend their perceptions. So, even when the courses were well underway, the process of stuffing my head with all the relevant passages from the books under discussion and concepts from critics and theorists (only one-fifth of which we could probably use in that class) still left me wound up beforehand. I’d arranged to have back-to-back classes, something normally detested, so that the anxiety of preparation and anticipation was condensed to a single part of the day. Yes, I had notes of all the fiction passages I wanted to refer to in class and, increasingly, I had overhead projections of the theoretical material. But instead of prepared lectures, I hoped in each class to choreograph a dance of those materials and the responses from my students and me. To switch metaphors, teaching was a bit like acrobatics without a net. No guarantees. An intense and focused process, rewarding but draining.

Class preparation and grading filled my evenings and weekends during teaching semesters. Research and writing, the internalized “publish or perish” imperative, filled my non-teaching semesters, although more flexibly. Until my medical leave, I hadn’t identified the thrum of chronic anxiety and self-reproach that hummed through my days. In academia, the sense of having done enough, in a day or a week or a year, never seems to come. My desire to be off-duty, the way many people are after a forty-hour work week, was another push towards retirement.

Increasingly in later years, classroom technology and systems for posting course materials and grades online kept changing, and changing more rapidly (three new systems in six years, the last one admittedly easier to use). That made leaving an appealing prospect too.

The pull to retirement

While these fatigues pushed me, dreams and desires pulled me towards retirement. Both ends of Dr. Doolittle’s mythical Pushmi-Pullyu were moving in the same direction.

My partner and I had good friends from ice-bound Minnesota, retirees who vacationed mid-winter in Key West or in Paris. Retirement would finally free us to join them on such adventures. With my partner’s health uncertain, enjoying time and travel together, while we still had time, appealed. Even the little byways of southern Ontario held unexplored possibilities.

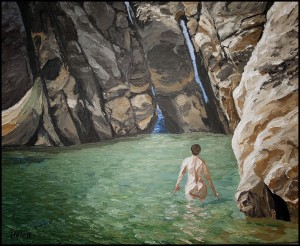

My painting too called for more dedicated time and attention. I had shifted from watercolour to oil painting, still working primarily on landscapes, and was particularly interested in using only a painting knife and no brushes to apply thick, impasto paint. I had dabbled in jewellery making, mostly making earrings, and was excited about more time to create. And excited about time for reading, for spiritual and personal growth, for cooking, possibly for writing. For leisure, something I’d seen little of in the previous stages of my life. Time to sit and talk or to gallivant with people in my world, family and friends who’d had to be squished into the corners of my days.

Retirement: The con list

The pushes and pulls of my Pros list were strong. But I had a Con list too.

Top of my arguments against retirement was the thrill of walking away after a successful class, exhilarated by the level of student perceptions and the weaving of arguments and evidence. An adrenaline high, that left me buzzing with yet more insights to share. Having bright young minds in a classroom is a gift, and I remember the pleasure of being able to tell one recent graduate class, “Every one of you in this group is smart – don’t let them tell you otherwise.” (I’d had my doubts about one of the class, and then she too came up with a shrewd observation.) So I learned from my students, and would miss the highs of that process.

In what turned out to be my last semester of teaching, one course, “Women in Literature” with about 120 students, had a long lab-style table across the front of classroom, putting me too far away from the students when I stood behind it. So I kept walking around in front of it, leaving all my page references, quotations, and other notes behind me on the table. And discovered to my surprise that I could teach almost the entire course, fluently too, from what was in my head (with the help of my own and the students’ overheads). In the same course, I finally resolved the problem of how to grade discussion participation fairly in large classes (or even small ones, given my memory issues). I invited all students each class to record their number of contributions (and for the shyer ones to hand in written contributions of what they would like to have said). These were the sort of satisfactions or discoveries I would be losing by retiring.

Particularly in the second half of my career, once feminism, postcolonialism, critical race theory, and queer studies had transformed my discipline, I had the satisfaction of feeling that my teaching and my research, but especially my teaching, were helping improve the world. In my classroom, students had to question things, to confront the limitations of their assumptions about race, gender, sexuality, class, colonialism, and power. When a feminist group to which I belonged decided to explore more activist possibilities, I realized that my idea of political action was something like street theatre, trying to influence the thinking of large numbers of people. Education, in other words. And that was what I was already doing. What I would be giving up.

Because work had been my identity for so many years, I was also worried about the disappearance of that meaningful role (just the pleasure of walking the campus as a faculty member during the weeks of family tours, seeing myself through the eyes of newcomers). I anticipated the loss of my place and colleagues within the profession. I feared that without the (excessive) demands of work, I might find that unstructured time felt aimless and less precious, that I might feel too much at loose ends.

Although my pension reduction for retiring two years early was to be half what it would have been the year before, it was still a substantial monthly amount. I kept trying to gear myself up to face the daunting stresses of two more years of work, with the argument of how much travel that money would fund every year thereafter for as long as I lived. Did I have the stamina to endure two more years?

Making the decision

My partner had taken a hands-off position about my retirement decision. But after a month of my consulting with friends and dithering with my Pros and Cons lists, he’d had enough. He declared that it was obvious, that I should simply retire. As soon as I had that affirmation, the Pros list looked overwhelming to me and the Con list shrank down primarily to the issue of money. I was freed to follow my instinctive impulse and recognize that in fact I was desperate to retire. To end the strain. Human Resources had my full attention. I sent in my retirement application.

Within a few months, I would be giving up the pressures, anxieties, and pleasures of the classroom, along with the consuming academic role that had defined me from young adulthood on. I would be following my pushmi-pullyu into new byways.

Helen, this article is thoughtful and interesting. I like the way you describe your process, and then at the end follow your instinct and intuition.