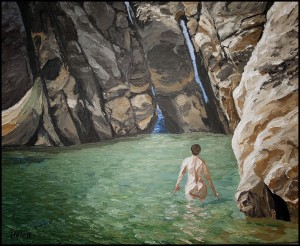

Helen, Heading Out (8)

A series of articles about recreating identity after an all-consuming career

By Helen

University Professor of English and Women’s Studies

Retired August 2012 at age 63

After discussing, with another retired professor, the satisfactions of my new painting adventure, I mentioned alternative responses to retirement, including just drooping and feeling lost. She said, “Especially men, for whom their work was their life,” to which I had to respond in honesty, “My work was my life.” “Mine too,” she acknowledged.

Bubbling over

When work is so central, its absence is bound to be noticed. On a family vacation recently, my oldest son asked what I missed.

“Teaching” was my first response. Not the grading or the anxiety of preparation beforehand, I explained, but being in the classroom sharing thoughts. “Ah,” he said, “just the good parts.” Two years ago my partner and I were invited to Dartmouth University to speak on a panel and visit a class on Native American literature. Having taught such courses and knowing I would no longer be doing so, I was bursting with a semester’s worth of ideas and quotations to be crammed into one class hour. At one point, I felt compelled to put my hand quietly on my partner’s knee to make time for me to speak. Eventually he had to put a hand on my knee to get me to be quiet in turn. One of the less familiar thinkers whose name I put on the blackboard turned out to be one the prof was planning to introduce the next class. I bubbled over in that classroom.

Stretching, pushing, and growing

Over the years as a professor, I refined the way I introduced concepts for the students. I found the right texts with which to begin the semester, lively, shorter, easier, but raising important issues. In my classes, I used teaching examples from previous courses, especially of what hadn’t gone well. And sometimes, new failures happened after those examples, and I had to build on them. For instance, a student, in teaching evaluations, complained of not being able to relate to novels by lesbians of colour. I used that criticism to teach ways of reading that ask how each of us is implicated in racial and sexual systems asymmetrically, in unequal but interlocking ways. When the next students mistook that as a call to identify with fictional characters different from themselves—“how do I know that I’m straight?”—I appreciated the stretching they were doing while pushing them further, to connect without reducing the differences. I was excited and rewarded by such improvements in the strategies I found to communicate. That sense of ongoing growth, of becoming better at what I did academically, is something I miss.

Because I had loved to learn, I always assumed that my students wanted to learn and were trying, even when at times apparently they didn’t and weren’t. Sometimes I agonized more over a grade than they had over the work. Having a class go well left me wired—excited and pleased– and I miss that. Even with the grandkids, I find that my primary impulse is to explain things to them, to want to teach.

Just the good parts

If I can focus on just the good parts, then there are parts of grading that I miss too. Essays were the best way to tell whether students really understood what I was teaching. Especially with senior and graduate classes, where the quality of analysis could be high, seeing the mental adventures of students was exciting and gratifying. I liked to see them applying and extending what I’d taught them but also surprising me and teaching me new ways of thinking. I had one fourth-year student who playfully subverted the conventions of citations and bibliography in her essay, because these too were expressions of power structures, which our postcolonial studies course was intended to identify and question. So with the assessing component removed from my experience of student essays, I might enjoy dipping into students’ written work again.

Forget the ivory tower

I have always found the notion of a rarified ivory tower of academia laughable. Universities are very much in the real world, and that is one of their virtues. Every semester I would learn of new challenges students faced: the suicide of a sister, the pre-existing condition that would cost a student in the U.S. $1000 for tubes in his daughter’s ears, the heavy work schedules needed to pay for university costs, the attacks of anxiety that made one young man’s face go as unformed as a toddler’s, the miscarriage attributed by her pastor to a student’s marital infidelity. I shepherded a student having a breakdown out of an exam and had to assure her, as we waited for health services, that angst about her grades could no longer be her prime concern. And sometimes I heard reports of more grandparent deaths during the last weeks of semester than was entirely plausible.

Regrets, I’ve had a few

Late in my career an older colleague in a nearby university inspired me with his new goal: to love his students. Every student carried a unique and rich inner life, and my fields of literature and women’s studies provided special opportunities to glimpse those worlds. Reading-response journals could be eye-opening. My opportunities for appreciation and connection were, alas, seriously limited by work pressures. I remember a graduate student, after one of my sabbaticals, asking if I was looking forward to the classroom and the disappointment in her face when I echoed every other faculty member in saying that it was hard to come back from time off. So realistically, some of what I miss was potential within my work, potential made almost unattainable by the very conditions of my work. I was usually too busy to appreciate, except in passing, the promise of my relationships with young people in the process of forming their future selves.

Writing: priceless

I have sometimes gotten out of bed to note down ideas for this column. It has reminded me of how much joy I take in putting ideas on the page. When my partner needs background information on wedding-dress styles or corporate malfeasance for his novels, I leap with enthusiasm. Research was always a part of article writing I relished. Actually writing literary criticism could be excruciating and slow, but the process of stuffing my brain and then waiting for analysis to jell was rewarding in the end. I came to understand why writers conceived the concept of the muse. If you are lucky, a moment arrives when you find yourself thinking above your weight class, when words seems to arise from somewhere beyond yourself. Priceless, as the MasterCard ads say.

I failed to fill my research potential as an academic. What with child-bearing and rearing, my medical leave, my slow writing pace and my early retirement, I produced fewer books and articles than I might have expected. At the time of retirement, I had reached a level of analysis where a high level of writing was within my grasp. One more, strong book would have rounded off my career nicely. Writing still is available to me, of course, and now I’m free to write outside the confines of my academic discipline. But having chosen to paint, I need to keep my focus clear. So I mourn a little the lost possibilities of literary creativity. And ponder the curious phenomenon, not unique to me, of people turning in mid-life or retirement from an area of strength to some new effort.

Pomp and circumstance

There is an authority and status that come with being a university professor. Although I resisted it in many ways – I went by my first name, not the title Dr., for example – the respect for my role was gratifying too. And now not part of my life. In particular I liked the excitement of being a prof on campus in September, as the students arrived. Although begrudging the time taken from an over-full schedule, I tried to attend the welcoming ceremony for first-year students, to see all the new faces, innocent still of how stressed they’d be in seven or eight short months. Even more I loved the drama of Convocation ceremonies, marching into an auditorium packed with graduating students and their families to a stirring trumpet rendition of, yes, “Pomp and Circumstance,” preceded by dignitaries carrying the University mace, we faculty tricked out in the robes, hoods, and mortar boards of our respective alma maters. I liked having this honour as a woman in a traditionally male profession, I liked contributing to the power of the ceremony for families who’d sacrificed for this moment, and I liked catching the eyes of students I’d taught and recognizing them on their big day. I could still participate in Convocation today—I just received a plea for more faculty to fill this fall’s procession—but would no longer know any of the graduates.

Making the world a better place

I am haunted by my own privilege and by the great injustice and human misery around me. One satisfaction of teaching was my sense that in raising questions of social justice and equality through literature or women’s studies, I was shaping students’ understanding and action in the world. Even though I wasn’t serving with Doctors without Borders, I was working for positive change. I was ethically engaged. Is it enough in retirement to have worked for change through one’s past career? Retirement, after all, is a time of greater leisure, when there is less excuse for political inaction.

The Art Gallery of Ontario had an exhibit recently on art as therapy, including the politics of art. One display, on a Claude Monet painting which had transformed what art could do, left me in tears. In claiming that Monet had created social change just by painting as he wished, without taking arms against prevailing values, the display spoke to my longing that art could be political. “Monet was not launching a fierce critique of the world; he was not trying to get people to see the errors of their ways or the injustice of existing institutions,” said the display. “He shows us what he loves, and tries to get us to share his delight.” I wish I could believe this claim, that love and delight change the world, that beauty is enough. I wish I could stop condemning myself for not making obvious contributions to the world. I wish I could believe that making beauty is a valuable enough offering.

In a similar vein, I discussed with my partner another friend’s retirement. “There’s enjoying yourself. And building good relationships with family and friends. But what about making the world a better place?” I asked. “Maybe that’s what makes the world a better place,” was his reply. I wish.

It’s okay – I’m retired

Three years into retirement, I had another version of that familiar teaching dream, this time of having forgotten to go to class for several weeks or to prepare the midterm exam. On the cusp of wakening, I was able to tell myself, “It’s okay. I’m retired.” I still struggle with the need for political engagement, but, mostly, looking back now over what I miss makes me feel good about my past career, without major regrets. Yes, my work was my life. But I’m creating a new body of work, and a new life.

Thank you for this piece of writing, Helen, and for the seven pieces that preceded it. You are thoughtful, insightful, and wise.

Thank you, Amy. It helps me to think these things out in writing too. And it’s good to know people are reading.