Helen, Heading Out (7)

Helen, Heading Out (7)

A series of articles about recreating identity after an all-consuming career

By Helen

University Professor of English and Women’s Studies

Retired August 2012 at age 63

In a questionnaire preparatory to a retirement workshop, years before the actual event, I identified relief as my anticipated feeling. What excited me was the prospect of time – for art, reading, people, cooking, travel, and personal growth. What worried me was the loss of my professional contacts and place, of meaningful roles, of structured days providing a sense of purpose. By the time I got to my actual pros and cons list for early retirement, I was attracted to the elimination of work stress and concerned about the sacrifice of pension money because of leaving early. So three years later, how has that all worked out?

Money, money, money, money

The money question sorted itself out easily for me, by comparison with many others, I suspect. My early-retirement buyout allowed us to pay off the bit remaining on our mortgage. After being told I didn’t qualify for U.S. Social Security despite having worked in the States for five years, I received a phone call out of the blue, from a civil servant whose African name Anu is also the Celtic name for the goddess of abundance. (In terms of the recent Crabapple Coaching article on relationships to money in retirement, I operate completely on a scarcity model.) Anu let me know that not only did my CPP contributions top up my Social Security, but additionally I was eligible for spousal benefits from my partner’s plan. Then my sweetie was awarded a number of substantial tax-free writing awards. So when I fret over whether I could have toughed out another two years at work for the extra 15% lifetime University pension, I remind myself that we have already been able to give away portions of that amount to friends and family over the past two years.

Intellectual curiosity

One of my friends, another professional woman, asked me whether I was managing to find outlets for my intellectual curiosity since leaving work. It wasn’t a concern I’d felt personally, assuming I’d turn away from what had sometimes felt like a pressure to prove myself academically, to strain after sometimes abstruse developments in literary theory. To my surprise I have found myself reading scholarly books in my field and monthly abstracts of journal articles. I do this from pure interest, no longer needing to keep up for teaching or publication. Last year, inspired by a New Year’s party where guests read each other poems we loved, I read a poem every morning, because I wanted to, working my way through the Oxford Book of Canadian Verse and the Norton Anthology of Poetry among other collections. I even wrote a few poems. Over lunch I now read books and magazines on painting. And I purchase art books for the bookshelf I’ve added to my studio. Having disbanded much of my library so that books no longer furnish my rooms, I turn to e-books and the public library for much reading – and I make discoveries. Returning to Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier, an old favourite, I was nonplussed to realize that the protagonist, while gratifyingly untrustworthy as a character, is not, as I had remembered, technically unreliable as a narrator. Working my way through the novels of Jane Austen, on whom I’d taken an entire graduate course, I found more romance and less moral depth than I recalled. And, having given away my battered paperback of Joyce Cary’s The Horse’s Mouth, I have so far been unable to find the book in a free on-line version. I read lots of detective fiction and other popular, contemporary works, especially Canadian fiction, as I always have, but am surprised and pleased to see that my work interests have survived as well.

The long half-life of a professional career

Letters in bottles from my former life in academia continue to drift in. I get requests for letters of reference from former students, though these have dwindled. I was delighted to provide a grad student elsewhere with insider documentation on the closure of University of Guelph’s Women’s Studies program, for her M.A. thesis. But I’ve had to redirect requests for supervision from prospective graduate students. I continue to receive inquiries about teaching in the Women’s Studies program, closed seven years ago and last under my coordination over a dozen years ago, as well as appeals for reviews of manuscripts and articles. The latter I could undertake if I wished, but don’t. I keep unsubscribing from online scholarly lists announcing conference and other academic opportunities. In the absence now of a professional allowance to fund conference travel, I find myself making more rigorous choices about possible presentations. Faced in retirement with the hefty fees and travel costs of a Vancouver fetal-alcohol conference appearance, I weighed it against possible vacation travel and chose not to go. Even when conference costs are funded, I am shifting my priorities about how I spend my time and life.

About two years ago my partner and I accepted invitations to speak at the University of Konstanz, Germany. That trip was one that we eventually abandoned, at least for the time being, as life got too full. But when plans were still underway and the topics of interest in Germany were Native literature and Alice Munro (just after her Nobel Prize), I did find myself regretting the thoroughness with which I had discarded my teaching notes. More recently a scholar mentioned the possibility of my contributing a chapter to a book on Munro he’s contemplating. Since I have further unpublished writing on Munro which could possibly be adapted, I am prepared to entertain the possibility. For the most part, however, such prospects come as reverberations from a past life.

Retirement has given me the distance to realize that I have had a writing life – and the only one I’m likely to get. I’ve not only had pressure to publish but also access to presses and an opportunity to speak to the world. In retirement I ponder what I might have written and realize that I have not necessarily explored what I might have preferred, were it not for the expectations and particular opportunities of my discipline (such as this recent Alice Munro request). When I mentioned this regret to another literary scholar, at an awards ceremony where she was shortlisted for the book she’d written in retirement, she reassured me that we were just too busy. Because of my commitment to painting, I don’t expect to make time for much more writing. Doors, though, remain open, back towards academic engagement, and sometimes I glance in that direction.

How’s that going for you?

As a younger academic, contemplating the question “Which book changed your life?” I toyed with the idea of replying, only somewhat tongue-in-cheek, “Dress for Success.” I learned just in time the urgency for women, especially young-looking, slight women like me, of a professional wardrobe in order to be taken seriously. As retirement approached distantly, I stopped buying suits and pantsuits, first sign of the change that was coming. I’ve been able increasingly to enjoy playful clothes, filmy and flowing tops and dresses, artistic costumes. My effort now is to make sure that I make room for them in my day, between my housecoat, my running gear, and my paint clothes.

When I hear from afar about new technological advances or restructuring and planning at the University, when I run into former colleagues facing classes and stacks of essays to grade, when I remember the necessity to be at work no matter what personal upheaval I might have been facing, I am relieved and happy to be retired. I miss aspects of my former life and will explore those in a column soon. But I have time these days to pull out a bird book and look up a bird I’ve seen on my run. I see colleagues locally and farther afield from time to time, and that suffices. I have time to travel.

My partner and I took a two-week trip to Uruguay in February of 2014, for example, in order to meet with writer and activist Eduardo Galeano, travelling there with colleagues who’d written a book about him. Although he could meet with us only once, Galeano was charming and eloquent, and clearly revered by others in the cafe. In Montevideo, we biked the Rambla along the coastline in the sunshine, I discovered sour cocktails called caipirinhas, we mastered the bus system, and then in Punta del Este we had days on the beach. To balance the picture, I was also irritable, an introvert in enforced companionship, a goal-oriented person without significant sightseeing or other objectives, in a metropolitan city going about its own business. Galeano died the following April, so the trip was well timed, despite being part of an overly busy year.

This past February I was free to accompany a bereaved friend for two weeks in Bradenton Beach, Florida at the condo she had been planning to revisit with her husband. Again, to avoid romanticizing, I should specify that my friend was sick almost the whole time as well as grieving, the weather was often moody, and instead of sketching as planned I buried myself in fictional trash. But I did discover the rusty piers which have become the subject of my latest series of paintings. And I was able to support a friend.

Creative reinvention

As I’ve explored in an earlier column, lack of structure and ensuing aimlessness have not been my challenges in retirement. A Crabapple Coaching workshop identified creative reinvention as one direction in retirement, an alternative to sticking with aspects of one’s former work, for good or ill, on the one hand or feeling lost on the other. Painting has become my form of self-reinvention. Before getting a studio, which I will discuss in a later column, I might have said glibly and self-critically that my commitment to painting puts me in my comfort zone, one of continual obligation and recurrent guilt. Here I am, in retirement and still feeling rueful about sleeping in. Still at the mercy of a puritan work ethic. Still not free.

A fellow painter and I joke, using another artist’s metaphor, about claw marks on the walls outside our painting room, about having to be dragged to our brushes. We both find, of course, that when we’re at the easel, the painting is compelling. And when my new studio eliminated the distractions of home, the temptations of household tasks and the Internet, claw marks on my way to the easel disappeared too for the most part.

I am nonetheless left with the quandary of whether devotion to daily painting is the right choice for me. Does painting, at my skill level and given the limited time I have to develop as an artist, warrant giving up other rewards of retirement? Am I painting because I love it or have I turned to art as another proving ground? Or both?

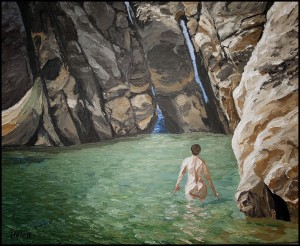

Painting does seem to put me in that zone of involved focus, where challenge and competence are reasonably balanced, where I am engrossed. The results often please me. I get encouragement from my partner, family, and friends too. While the passion to paint is supposed to be sufficient in itself, I’ll acknowledge that extrinsic reinforcements help with my decision to commit myself. Painting then has replaced the structure my work used to provide, while feeling more completely self-directed and simply satisfying.

So far, so good…

Note: Helen and her partner will soon depart for almost four weeks in Europe, centred on a river cruise. Helen will be taking a month-long break from writing for this column. You could say that she’s heading out.

Interesting to be reading this article and newsletter in the dark with my balcony open to the night air and stars, on our first evening sailing down the Danube, having just passed the lights of the castle on a hill. Retirement can be a gift.

So lovely to read your comment, Helen. Such a well earned retirement moment for you.