Helen, Heading Out (11)

Helen, Heading Out (11)

A series of articles about recreating identity after an all-consuming career

By Helen

University Professor of English and Women’s Studies

Retired August 2012 at age 63

This is Helen’s final article for this column.

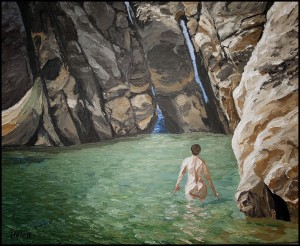

The beauty of cross-hatching

Isn’t growing older the same thing as living longer? (TV ad)

When I met friends in Lethbridge whom I hadn’t seen in 15 years, I saw them through a shocking scrim of aging. Then the new image clicked into place. My own face was presumably the same shock to them. As it can be to me.

Even before I had a vested interest, I resisted our culture’s over-valuing of youth in phrases such as ‘young at heart.’ Why wouldn’t ‘old at heart’ be the commendation? But that’s theoretical, and I am after all part of my culture. I do, nonetheless, have my strategies for staying positive about aging.

I see people, and myself, react with surprise and appreciation to earlier photos of themselves. “But I looked so good,” we say. “And I didn’t realize it.” So I try to anticipate such later reactions to my current face, by measuring backwards from the end, not the beginning. Anticipating my aged face, I remind myself of how fresh-faced I currently look by comparison.

But I also actively fend off the anti-aging cosmetic industry by trying to value wrinkles, just as years earlier I reframed my caesarian scar and adhesions as battle scars. I look with appreciation at the cross-hatched faces of June Callwood, of Holocaust heroine Irena Sendler (who saved 2500 children and lived to be 98), and of my good friend Nellie. Yes, the strength and sweetness of their faces, but also the cross-hatching. Of course, good bones help.

General motto: find and value role models and images from among the aging. And the very old.

The times they are a-changin’

Life is routine and routine is resistance to wonder. (Abraham Joshua Heschel)

Time speeds up later in life. Two days ago I filled my weekly pill dispenser, and today it needs filling again. “Where did October go?” becomes “Where did 2015 go?” I read an article recently on why time flies, on how routine is the culprit, causing us to pay less attention to what we’re doing. Being in unfamiliar circumstances slows time for us. My partner and I actually used this as an argument for our six-week European trip. It does work.

Routines are admittedly reassuring and effective, and free our brains for other work. My new routine is the closing down of my studio each night (the palette, the brushes, the cell phone, the I-pod, the heater or fan, the lights, the locks). This routine pleases me and saves me grief. But the goal of making my final decades last longer may be a reason to vary my route to the studio, shop in a different store, listen to new music . . .

No more cleaning

Life is hard and then you die, the old saying goes. On the positive side, life is hard and then you die, and then there’s no more cleaning.

When she was planning her funeral, my mother fretted over the question of a concrete burial vault. She didn’t need one, but it would prevent the grave from slumping and make mowing easier for the groundskeeper. “You can stop taking care of people once you die, Mum,” I told her.

Sometimes I imagine eventually reaching a level of fatigue where I would just leave some jobs to others after my death. Realistically, that might be because I have to, rather than because I choose. Friends who have had to clear out homes of hoarders are already purging their own places, to spare their kids.

The appalling snow

She died. She is dead. Is the word so difficult to learn? (C.S. Lewis, “A Grief Observed”)

We built our story-and-a-half house as a bungalow basically, with all living possible on the main floor, with wheelchair-width doorways, and with grab bars in the showers. The prospect, though, of someday being unable to climb to the upstairs shower is seriously disheartening.

But death is the real specter, both my death and that of my loved ones. And when I’m hit with sudden terrible glimpses of this prospect, my attempt here at containment feels utterly inadequate. So this column is not the grand explanation, just current notes from the front.

As I fill in my new 2016 day timer, I find that, along with birthdays, I’m entering more new anniversaries of deaths, to support those left behind. My address book too contains little landmines – entries or scratched-out entries for friends and family members who no longer exist.

I have watched the anguish of a friend over the two years since the premature death of her husband. And I buckle at such a future. Death and loss I’ve identified as triggers for depression, for seeing life as a downward spiral. It doesn’t end well, I tell myself.

The immensity of the gift

And did you get what/ you wanted from this life, even so? (Raymond Carver)

That’s when I have to turn to my cognitive-therapy reminders that if I’m finding the world unsafe and painful, I’m probably over-emphasizing the losses. I remind myself that the immensity of the grief is a measure of the immensity of the gift. As Julian Barnes says about mourning, “It hurts just as much as it is worth.”

I have heartening examples of good lives lived in the shadow of death. My father, recovering in old age from painful hip surgery after walking on a broken hip for five weeks, said, “I haven’t reached despair yet.” A bit later he exclaimed, at 90, “I don’t want to be on a cane for rest of my life!” And wasn’t. Even when he had weeks to live, he maintained his equanimity. About his imminent death, I said, “We’re going to be very sad,” He said, “I won’t be there for that,” going on to ask whether the birdfeeder he could see was on his neighbour’s side of the fence or beyond it.

At a library book sale this fall, I ran into a retired professor of history and asked him how life was going. Despite unspecified “health problems” (he’d had prostate cancer, I knew), he was enjoying writing and grandkids. Gesturing outside, he called on the autumn burst of colour as an image for this life stage. I’d been thinking exactly the same thing and said so with enthusiasm.

Although we have the metaphor of the swan song for a final flourishing, most conceptualizations of aging emphasize deterioration and decrepitude. Yet all around us in this part of the world, nature offers us another model. Never are the trees more glorious.

Pero es la vida

we are all going to die, all of us, what a circus! that alone should make us love each other but it doesn’t. (Charles Bukowski)

I have noticed my partner become more demonstrative and thoughtful over time, as mortality makes itself felt. My neighbour speaks of revising his sense of what really matters, of appreciating a smile between people. (When Leigh learned in Guatemala of his mother’s death, the man who brought the news said, “Lo siento; pero es la vida. I am sorry; that is life.”) Living more meaningfully in the face of impending death becomes a new life stage.

Another change I’ve noticed is that certain risk factors and possible deaths, for me and my partner, by heart attack, for example, now inspire not dismay but a more sober assessment. Since we all die somehow, that might not be a bad way to go. Compared to Alzheimer’s or a stroke, say.

A friend, whose family history is one of early heart attacks, makes sure she hugs everyone well after each meeting, but has no fear of ceasing to be. My brother-in-law anticipates dying with interest, as the last frontier. (His wife, my sister, with much less equanimity, refuses to think about death, arguing that even reincarnation would be no solution if you are unaware and therefore aren’t your previous self.) Like most in my circle, I have no hope of personal immortality and must increasingly find ways to face this final ending.

Notes from the front

Into many a green valley/ Drifts the appalling snow. (W.H. Auden)

I’ve developed three ideas about death, to try to reassure myself. Perhaps it’s like leaving the party alone. That interim moment is a lonely one, outside on the dark steps, cut off from the good times, but it’s just a transition, and once home, I’m fine alone. The moment itself is hard, not thereafter. (“Home” in this analogy is likely nothingness, but still.)

When my mother was dying, I tried to reassure her and myself by comparing death to falling asleep watching a good television show. The program is gripping, but eventually fatigue wins out, and drifting off is even more compelling.

My third idea is more fanciful and desperate, in the face of annihilation. Perhaps, I tell myself, there’ll be no “I” but possibly a “we.” Given what physics keeps revealing about connections at subatomic levels, perhaps we join a cosmic dance of atoms and light.

Potential consolations

What you were goes on in the world. You just don’t go with it. (Steven Price)

I also turn to a version of the Blackfoot story about the origin of death, in which Old Woman and Old Man debate the alternatives. Old Woman chooses death for people, so that room is made for babies and new lives. At some level, I can be comforted by this reasoning (though I have my own, separate quarrel with the design of birthing).

Old Woman adds that death will bring sympathy into the world. When I have my momentary appalled glimpses of death, I embrace rather than repress them, because they help me treasure what I have. “We are going to die, and that makes us the lucky ones. Most people are never going to die because they are never going to be born,” says Richard Dawkins.

My own pagan spirituality reminds me of my place in the cycle of the seasons and in the cycles of the sun and moon. Every day I invoke the sequence of “Birth, initiation, love, repose, and death, with transformation at the centre.” It doesn’t save me, but it comes closer to consolation than promises of immortality that I can’t believe.

Nature endures

In the end – I must believe it – just like a salmon, I will know how to die, and though I die, though I lose my life, nature wins. Nature endures. It is strange, and it is hard, but it’s comfort, and I’ll take it. (Eva Saulitis)

So here I stand, horrified at prospects ahead, perhaps more than some people, but scouting about for how to live with aging, bereavement, and eventually dying.

For now at least, retirement is proving to be a gift. Without the necessity to earn money, which constrained both my time and my choices, and without child-rearing responsibilities, this stage offers me new freedoms. My work and my children were satisfactions of my summer. Now my leaves are turning coral and gold.

I love this thought: “When my mother was dying, I tried to reassure her and myself by comparing death to falling asleep watching a good television show. The program is gripping, but eventually fatigue wins out, and drifting off is even more compelling.”

But I have to say that to focus on death in your “final” column for this newsletter is a little overwhelming for me. I hope we will hear from you occasionally in the future!

I do hope to pop in from time to time, Amy, should new thoughts and experiences of retirement call out to be shared.

I’ve come across two more quotations relevant to this column.

Regarding

reminders of the appalling snow, Carson McCullers says, “There’s nothing that makes you so aware of the improvisation of human existence as a song unfinished. Or an old address book.”

But then, Anne Boyer offers this reassurance, “It’s not just our errors we become brave about, but our projects’—and our own—incompleteness. You can stop fearing death, too, if you begin to think of the collective project of being alive in the common world, that one’s own end and the end to one’s work and one’s love is not the end of what is right or good. What needs to go on will.”

The optimism in Anne Boyer’s thought is reassuring. “What needs to go on will.” Thanks, Helen.